Early communication networks

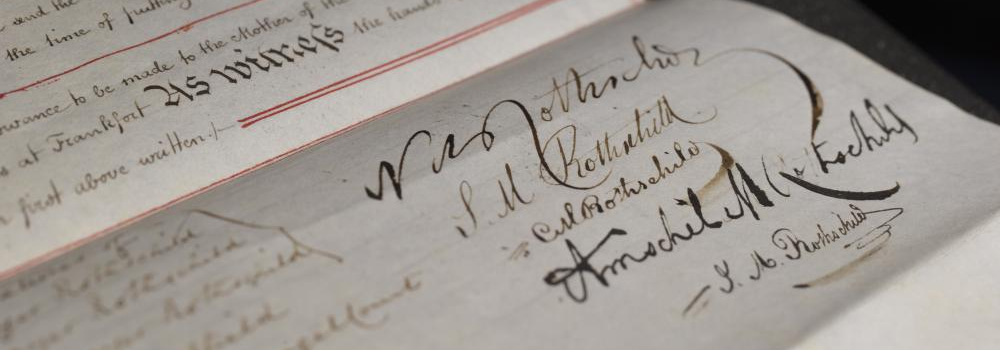

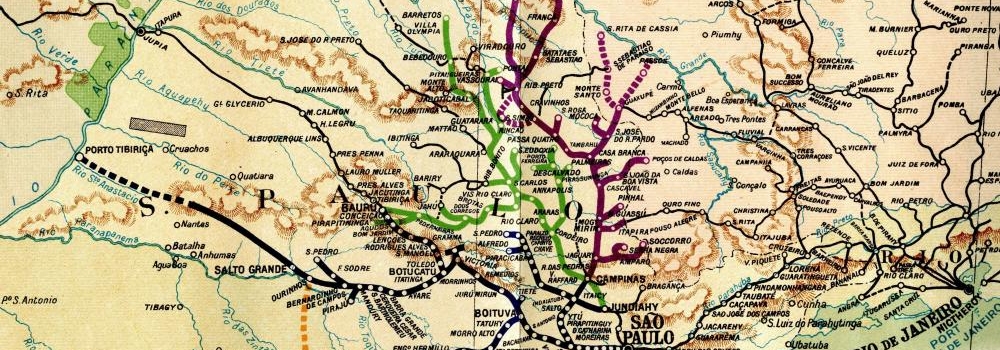

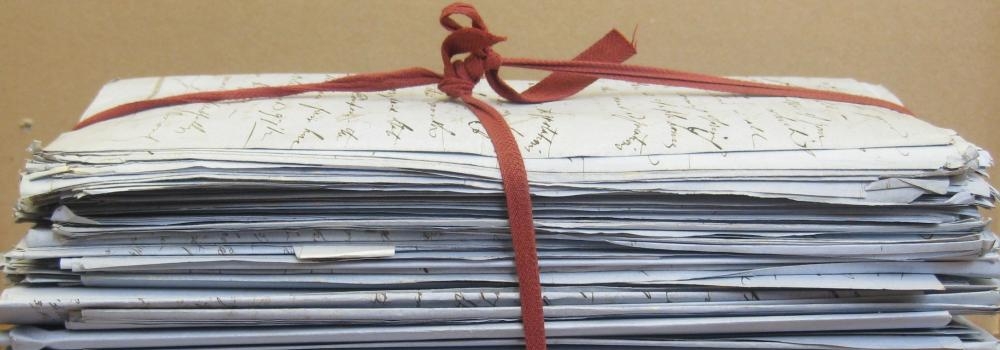

Efficient and accurate communications were essential to the Rothschild early business success. By 1812, the year of Mayer Amschel Rothschild’s death, the five brothers had grown used to travelling throughout Europe on business, and the importance of worthwhile up-to-date commercial data was crucial. To make the most of what they found on their travels, they developed the habit of writing detailed letters keeping their siblings abreast of what was going on in their sphere, whether it was the day’s business, the market opportunities and prices in the towns they passed through, or just the usual family comments on their brothers’ behaviour and character. Getting these letters delivered swiftly and securely was another matter. In an age when a postal system was developing at differing speeds and with varying efficiency across Europe, the Rothschilds relied on a network of trusted couriers.

Letters carried by pigeon

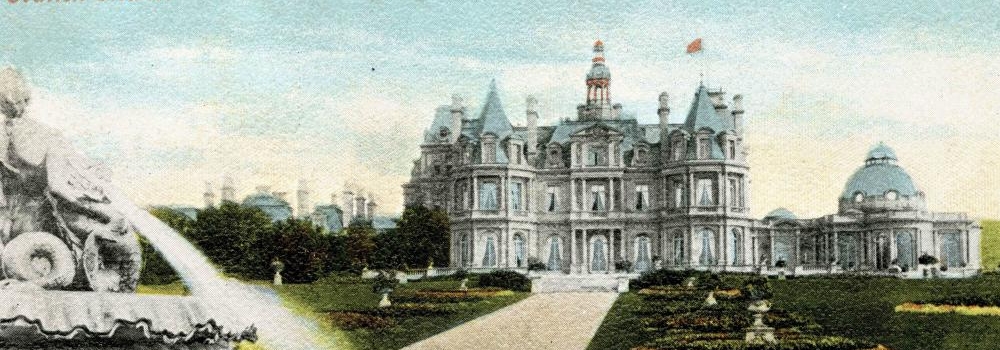

Certainly by the 1840s the brothers had taken to the use of pigeons to carry short and important messages between them. There is no evidence that pigeons were kept at New Court (or elsewhere), but Nathan Rothschild paid £8,750 for Burmarsh Farm, near Hythe, in Kent, and this may have been a base where pigeons were stationed; evidence in the Archive indicates that Burmarsh Farm was on the books of the London bank until at least 1918, although it may be that the property was retained for its rental value long after its original need ceased. Further support for this theory is to be found in The Times, 3 August 1836, which reported that the first intimation in England of the death of Nathan Rothschild was when a pigeon shot down in Kent was found to have attached to its leg a roll of paper inscribed with the words: ‘Il est mort’.

A letter written on 28 August 1846 by Nathan's son Nathaniel (1812-1870) from Paris refers to the use of pigeons (XI/109/57). Two examples of messages carried by pigeon dating from 1846 also survive (RAL XI/109/57). They measure about 8cm by 5cm and still bear the folds where they were packed into the small container attached to the pigeon’s leg. The reason for such few survivals is that these messages were instructions for a particular course of action, rather than documents in their own right to be retained. The information may have been copied upon receipt, (a clerk may have been stationed on a rotation basis at the place where the messages were received) and it was the fair copy of the resulting document that was despatched by rider to New Court, and the information from the message may then have been recorded elsewhere in correspondence or a ledger. The original pigeon message was probably destroyed shortly after receipt, either for reasons of confidentiality or because it was simply no longer needed, the information it contained having been acted upon. We may speculate that the examples that survive in the Archive contained information that was time critical, and therefore the message was itself immediately relayed to New Court, or that they were kept as curios. It is highly unlikely that Nathan or any of his brothers would have had any direct contact with the messenger pigeons; this would have been done by clerks, porters and other staff.

Part of the success of the Rothschild’s communication system was its flexibility, using a number of different means of transmission, including pigeon post, to suit the circumstances.

News of ‘Waterloo’

Whilst it is true that the Rothschilds had an extensive communications network, and did use messenger pigeons, there is no evidence for the news of the English victory at Waterloo having been brought to New Court in 1815 by pigeon post. No original contemporary account or documentation concerning how the news reached New Court survives in the collections of the Archive. Recent research has also cast new light on this persistent myth. See Brian Cathcart, ‘Nathan Rothschild and the Battle of Waterloo’, Rothschild Archive Review of the Year 2013-2014 »