In the Archive is preserved a file from the Staff Department of N M Rothschild & Sons, concerning staff matters 1874-1915. It contains lists of employees, dates of service, positions held, salaries, wages, allowances and bonuses paid to staff, details of pension payments and income tax payments, and details of terms and conditions of employment.

A New Court clerk

The term clerk is derived from the Latin ‘clericus’ meaning ‘cleric’, an association derived from medieval courts, where writing was mainly entrusted to clergy because most laymen couldn't read. Clerks performed a number of important roles in the smooth running of the business at New Court.

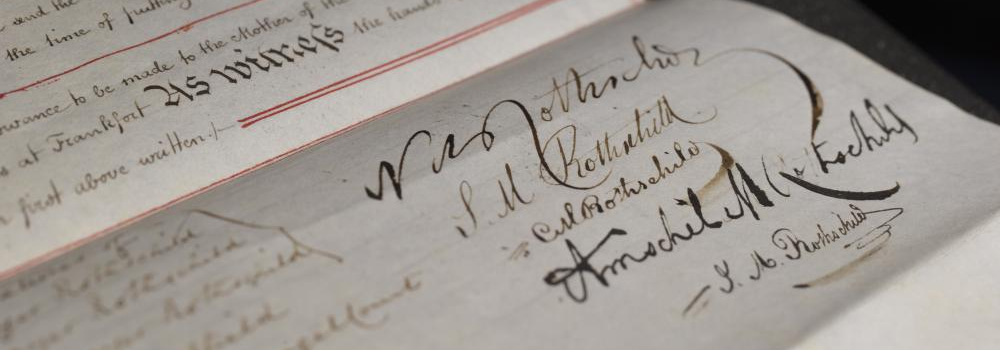

Within the Victorian and Edwardian social class, the bank clerk held a particularly privileged position. Recruitment into the Bank was invariably based on personal recommendation. Clerks had to demonstrate technical competence in arithmetic and bookkeeping, and good handwriting was viewed as an essential tool for a successful career. Careful penmanship served both legibility and minimised the correction of errors, as the erasing errors in the Bank’s books was a practice generally frowned on due to its potential use for concealing fraud. When Mr Leo Kelly arrived as a clerk in 1915, he found only one typewriter in the whole office. For N M Rothschild & Sons, the bank’s influential role extended far beyond the immediate confines of the business, and employees hired by the bank had to beyond reproach, since financial stability could be equated with good reputation and character.

However, if the moral expectations of employment with the Bank were demanding, the potential rewards provided generous compensation. There were good opportunities for career advancement, and once a clerk had achieved a position of seniority within the Bank, he could retain this situation into old age. Bank clerks were among the highest paid clerical workers and had the potential to earn significant salaries with advancing seniority. Rothschild clerks were paid quarterly. In 1874, clerks were paid an annual salary of £200, approximately £16,000 today. By 1911, a senior clerk could earn around £800-£1,000, £73,000-£100,000 today. Ronald Palin, a clerk in the 1920s recalls annual bonuses, tips and other presents given out at Christmas and for summer holidays.

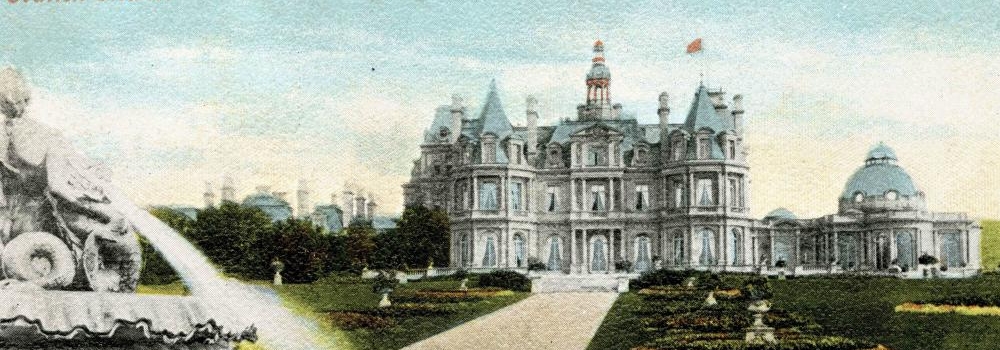

There were other non-monetary advantages to the position; clerks generally worked shorter hours than most other clerical staff, (although the clerks at Hoare’s bank humorously referred to themselves as the ‘Association of the Sons of Toil’), and, in the early 1860s, the staff of N M Rothschild & Sons moved into the newly rebuilt New Court. In the style of an Italian palazzo, the new building offered large windows providing good natural light and spacious wood panelled offices. Until just after the First World War, the whole staff, numbering well under a hundred, was given lunch on the premises in the Clerk’s Dining Room.

Women clerks

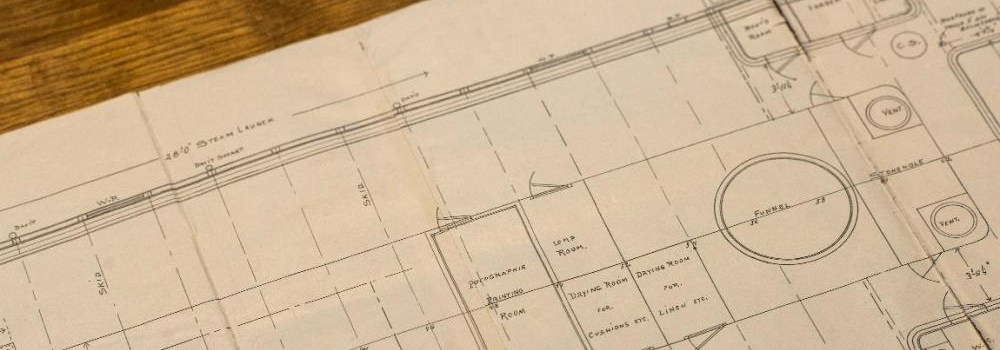

Women did not enter the ranks of clerks in the City in great numbers until the 1920s and 1930s with the advent of typewriters, telephones and other office equipment. However, in the employment of women, N M Rothschild & Sons led the way, employing 'lady clerks' well before this date. Female clerks were particularly skilled at counting bond coupons rapidly and accurately. Most female employees were unmarried, and strictly segregated from their male colleagues; they were housed in offices at the top of the building, and a plan of New Court from the 1920s shows a dividing wall between the 'Male Clerks’' and 'Women Clerks’' Dining Rooms.

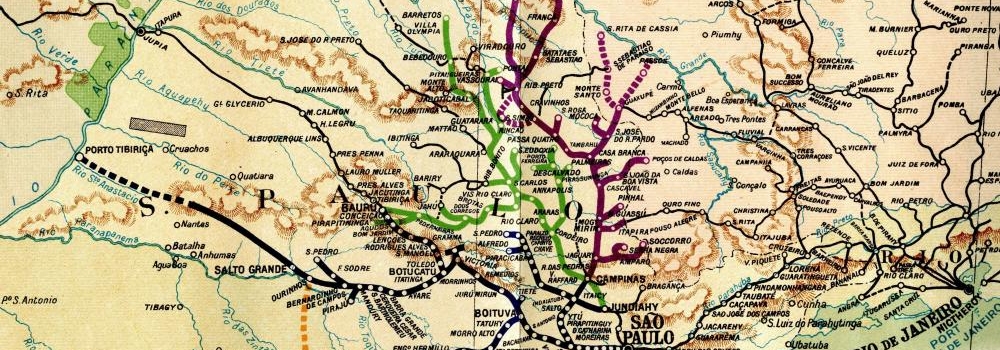

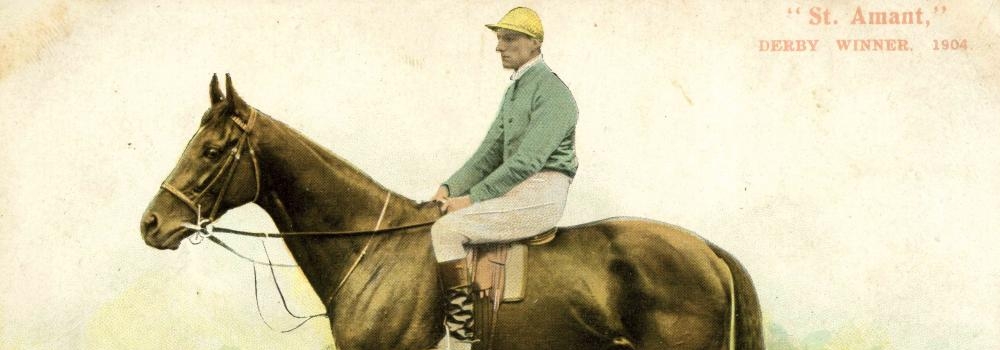

A job at New Court was a highly sought after position, offering security in a very insecure world. For many clerks in Victorian and Edwardian London, a city which was gaining from the growth in international trade, domestic consumption, the spoils of empire and the seat of government, the period was one of modest progress; a clerk could afford to rent or buy one of the new elegant terraced villas in the suburbs of Brixton and Clapham, or the expanding ‘Metroland’ of north-west London, easily reached by fast electric trains. A clerk could afford a daily maid or an evening cook. If a man had enough initiative and energy after the working day, he could attend evening courses on scientific subjects or Latin or shorthand at one of the many London colleges and institutes. At New Court, staff could join the St Swithin's Amateur Dramatic Club, and the St Swithin's Musical Society.

The Diary of a Nobody by George and Weedon Grossmith, published in 1892, humorously records the daily events in the lives of a London financial clerk, Charles Pooter, and his wife and son. Ronald Palin, who joined N M Rothschild & Sons in 1925, eventually rising to the position of Secretary of the Bank, recalls his time with the firm in Rothschild Relish (Cassell: London, 1970), an affectionate portrait of the unique world of New Court.

RAL 000/2067 (12/1)