In today’s fast-moving business environment, rapid access to accurate intelligence is critical. Protecting our information assets, and the data entrusted to us by our clients and partners is the responsibility of us all. In the digital age, systems need to be robust to prevent data breaches. But protection of information is not just a 21st century phenomenon. Read on to discover how the Rothschild business has historically employed methods to keep data safe and secure.

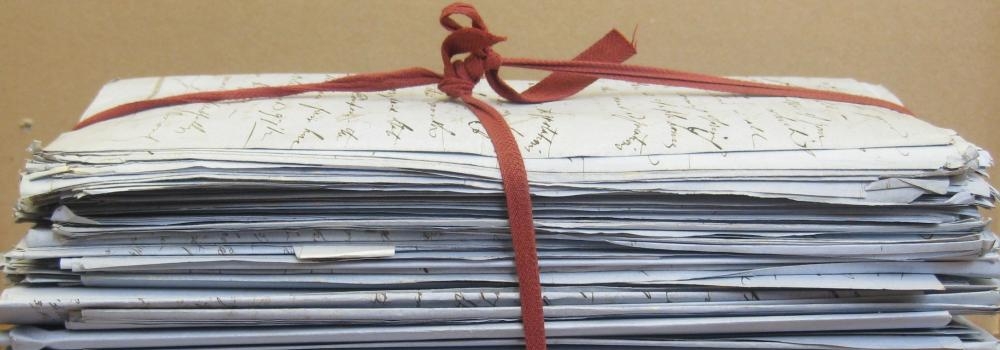

Letters

“Be careful with letters here because people are curious to know whether we have any secrets.” Carl Rothschild to his brothers Salomon and Nathan, written from Berlin, 10 December 1816

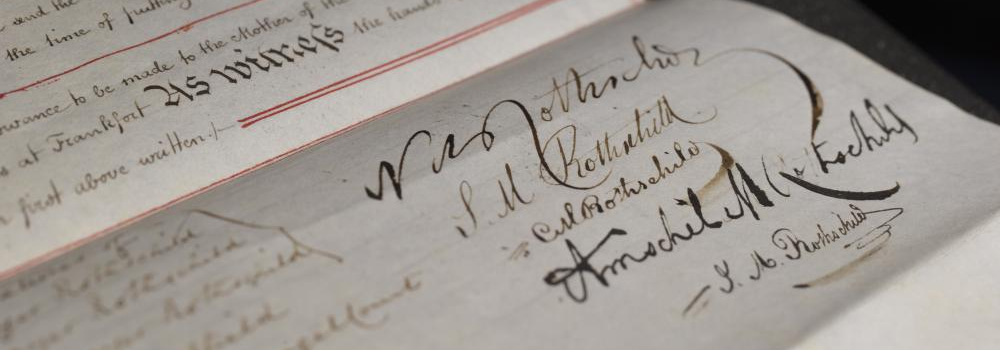

The five sons of Mayer Amschel Rothschild (1744-1812), who travelled throughout Europe in pursuit of the family business, wrote daily to one another, their detailed letters keeping their siblings abreast of what was going on in their sphere, whether it was the day’s business, the market opportunities and prices, or just the usual family gossip. Judendeutsch (words written in the German language and committed to paper in Hebrew characters) was the language in which the brothers were educated. The use of this script for their letters provided a useful means of protecting their missives from prying eyes, for although not in itself a code, the comparative rarity of understanding of the script meant that they could not easily be deciphered. Add the use of code-names for the key people they were discussing, the highly individual handwriting of the brothers, and the consignment of letters to a trusted private courier network, and you come close to the whole system being spy-proof.

Pigeon post

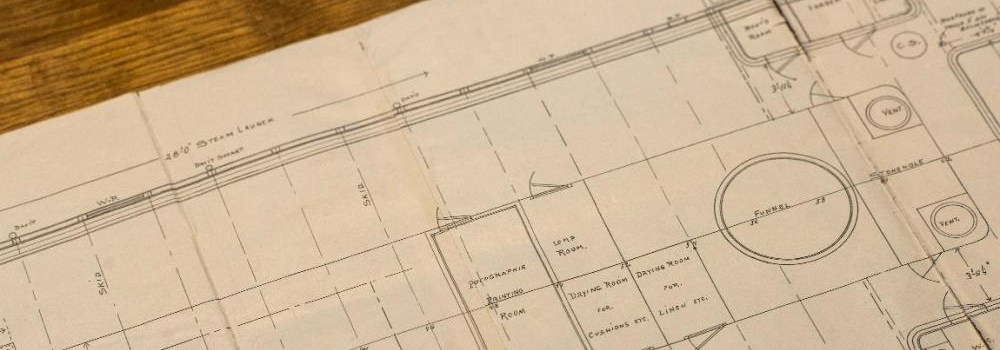

We can be certain that by the 1840s - and probably much earlier - the brothers had used messenger pigeons to carry short and important messages between them, although the story that pigeons first brought the news of the English victory at Waterloo to New Court in 1815 has not been authenticated. Nathan Mayer Rothschild (1777-1836) purchased ‘Burmarsh Farm’ in Kent where pigeons were probably stationed; this property was on the books of the London bank until at least 1918. A letter written in August 1846 by Nathaniel de Rothschild (1812-1870) from Paris (Nathaniel was Nathan’s son) refers to the use of pigeon post: “I hope our feathered messengers will have brought you in due time our good prices.”

Telegraphic code

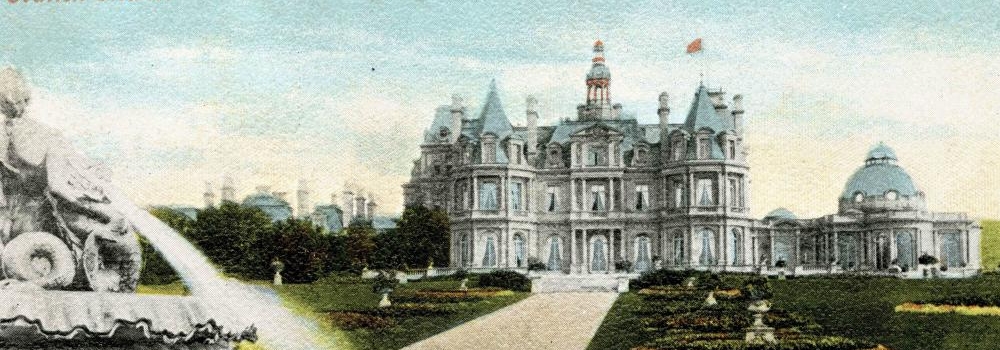

In 1850, Paul Julius Reuter approached the Rothschilds in London, seeking them as a client for a new service he was developing, to speed information across Europe with the latest technology. Within months, Reuter had moved to London and set up in offices only two minutes from St Swithin’s Lane. N M Rothschild & Sons became early and effective patrons of Reuter’s telegraph, using it to send coded messages to and from their agents and counterparties around the world. A new generation and definition of speed had arrived.

The first telegraphic codes were developed shortly after the advent of the telegraph, and spread rapidly; by 1854, one eighth of telegrams transmitted between New York and New Orleans were written in code. Code was used to save on cablegram costs, as telegraph services commonly charged per word sent, and companies which sent large volumes of telegrams developed codes to save money on fees. From the 1870s, elaborate commercial codes which encoded complete phrases into single words were developed. Commercial codes were not generally intended to keep telegrams private, as the codes were widely published; they were cost-saving measures only. Another aim of the telegraph codes was to reduce the risk of misunderstanding by avoiding having similar words mean similar things; codes were usually designed to avoid error (which could be costly) by using words which could not be easily confused by telegraph operators.

Private codes developed to provide an additional level of privacy and security; most banks used codes for telegraphed messages. As the work of the Rothschild banks began to be entrusted to an army of clerks, the use of code became more formalised and more complicated. Some of the Rothschild code keys have survived. A coding clerk in any of the Rothschild banks would work with a whole file of individual codes, one for each of the different Rothschild agents around the world. August Belmont & Co. in New York might write “Ankle Antic fifteen”, meaning “Pay 1315” (Ankle = pay 1000; Antic = pay 300). One extraordinarily complex code, in use in the Paris bank of de Rothschild Frères, allowed for the substitution of whole sentences. For example the message “The British Government will persist despite opposition in the House” becomes, by way of the code book “The bonds have already been sent to Alexandria”. One begins to wonder how many sentences in Rothschild letters, so far taken at face value, carry completely different meanings from those on the page? Does a century-old code continue to fool the archivists and historians of today?

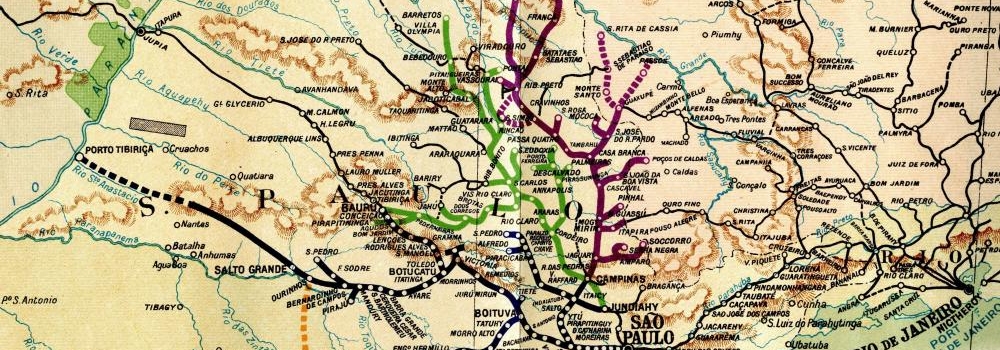

Later code books survive, used extensively for South American business, c.1910-1938. These volumes list telegraphic codes (usually three digits) and their meanings; ‘116’ meant ‘We will effect shipment and insurance’. Michael Bonavia, a junior Rothschild clerk in the 1930s, recalled “during one week in four, I, in turn with other juniors was required to be on early duty to decipher the overnight cables before the office opened at ten. This could be interesting: it introduced me to the use of commercial codebooks which enabled nearly all the ordinary phrases used in business to be cabled economically by single five-letter words, meaningless in themselves…” From the late 1950s, the arrival of the ability to make transatlantic telephone calls and next-day airmail rendered telegraphic codes obsolete, and heralded the search for speed and security of information-exchange which has brought us to our present levels of demand and expectation.

RAL XI/19