The part played by Nathan Mayer Rothschild (1777-1836) and his brothers in helping the British Government to finance military operations against Napoleon is legendary. Nathan's London House, N M Rothschild, dealt in bullion and foreign exchange, and his remarkable successes in these fields earned him the contract from the British Government to supply Wellington's troops with gold coin in 1814 and 1815, leading up to the Battle of Waterloo.

“That was the best business I ever did” is how Nathan described in a famous after-dinner conversation his involvement with Wellington, when between early 1814 and the Battle of Waterloo in 1815 he and his brothers brought together huge quantities of coin to finance Wellington’s army in their campaigns up through Spain and into France. Wellington had, since 1809, with increasing urgency, been urging upon the British government the need for funds in locally useable form to avoid disaffection. Herries, the Commissary-General turned to the young Nathan Rothschild and gave him his ‘big break’.

After the 'Waterloo commission' Wellington continued to hold the highest opinion of Nathan, and the House of Rothchild. In the Banking crisis of 1825, when, with the injection of large volumes of bullion, Nathan saved the Bank of England from a potential crash, following a run on several country banks and a consequent loss of confidence, Wellington declared “Had it not been for the most extraordinary exertions – above all on the part of old Rothschild – the Bank must have stopped payment”. The Duke held an account with Rothschild for a while, though the balance sheets show that he did not make much use of his overdraft facility.

The death of the Duke of Wellington

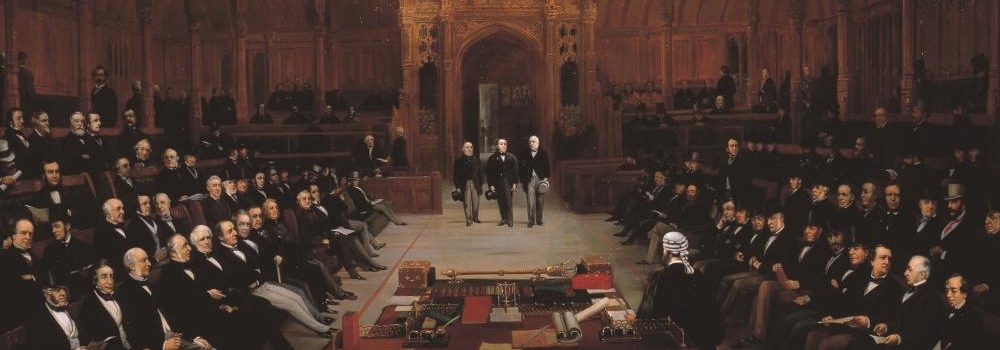

Wellington died at Walmer Castle in Deal on 14 September 1852, aged 83. On 18th November 1852, the Duke was laid to rest in St Paul’s Cathedral. Nearly half a century after Nelson’s ceremony and almost four decades of relative peace across land and sea following Waterloo, Wellington’s state funeral was the most extraordinary street procession that Londoners could remember. Prince Albert took the lead in planning a funeral of unparalleled magnificence, arranging a lavish lying-in-state at Chelsea Hospital, followed by the transfer of the body to Horse Guards and then a meandering two-mile procession from Horse Guards to St. Paul’s. The funeral pageant cost £80,000.

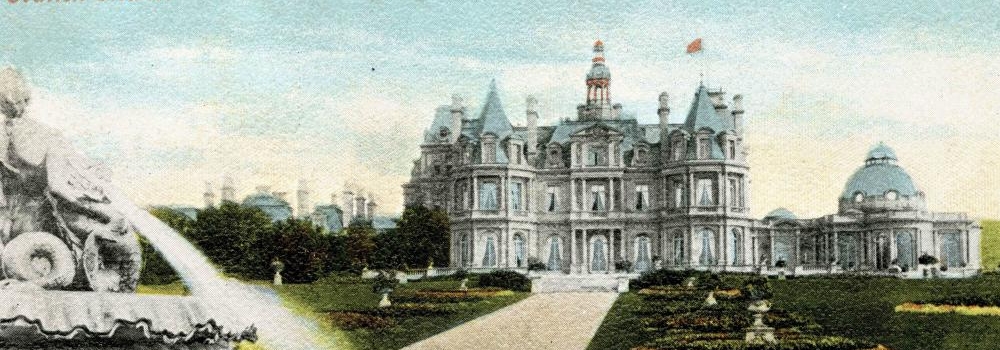

On that sombre day in 1852, the Rothschilds may have watched from the windows of 148 Piccadilly as the huge crowd below witnessed the passing of the 1st Duke's funeral cortege, for in 1844, Baron Lionel de Rothschild (1808-1879) had acquired 148 Piccadilly as his London home. In doing so, he became next-door neighbour to Wellington at No. 1, London, Apsley House.

This hand coloured print (which folds out to over 2m) of the funeral procession was one of many such souvenirs produced for this major state event. It was pasted into a scrapbook in the library of Nathaniel, 1st Lord Rothschild (1840-1915) at Tring Park.

Queen Victoria, was deeply moved, writing to her uncle Leopold a few days after the funeral, “I cannot say what a deep and huge impression it made on me! It was a beautiful sight. In the Cathedral it was much more touching still!”

The future Prime Minister William Gladstone, too, wrote in his diary of the “solemn & magnificent procession” in which “the most nobly & touchingly conceived part of all was the slow lowering of the coffin, surmounted by the Duke’s coronet & baton, his Military hat & sword, while the organ played the dead march”.

RAL reference: RAL 000/1323/38/1