In today’s fast-paced world where emails are delivered in micro-seconds, and groceries, clothes and even automobiles can be ordered and delivered to your home in a matter of minutes, we look back 200 years to a time when the transport of mail and goods was a much more complicated affair. Travel with us to the extraordinary and often dangerous age of the mail coach.

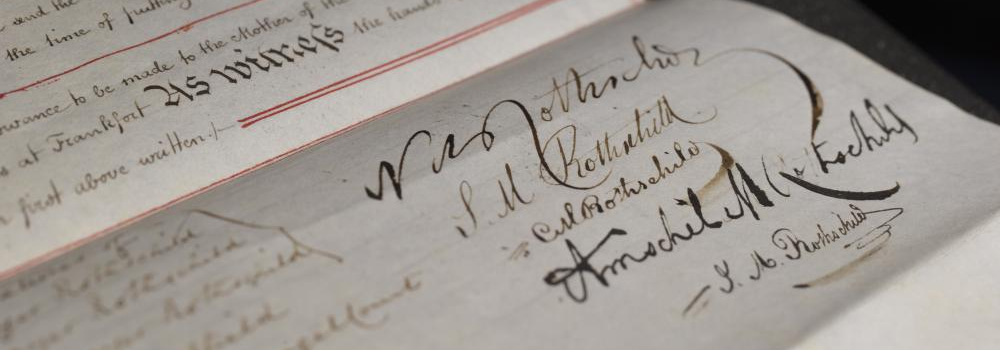

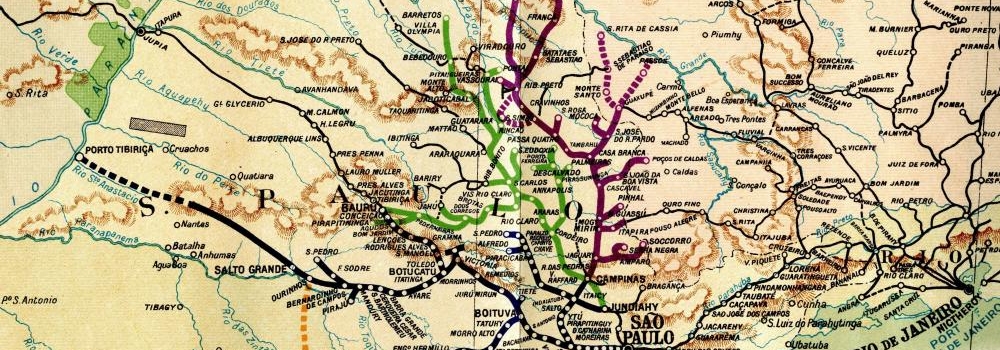

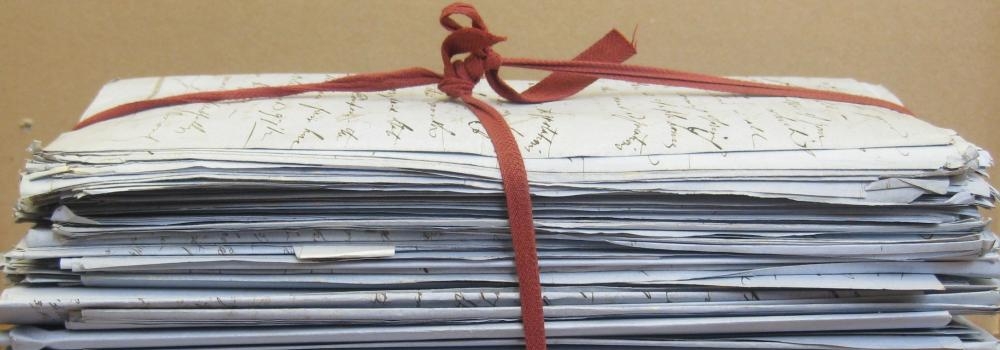

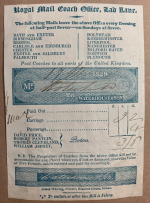

In the nineteenth century, Rothschilds' own system of communications was a world beater, enabling the family firm to maintain a convincing lead over its rivals through the quality of its information and the speed with which it could be transmitted. Until the invention of the mail coach in the mid-1780s, getting mail and deliveries was time-consuming. A rare survival in the collections of the Archive is a small volume into which are pasted examples of an early form of advertising – mail coach bills. The origin of the collection is unknown but may have been gathered from old bills found at New Court, dating from the time when the firm patronised the mail coach service. Mail coach contractors would place advertisements such as these in newspapers and circulate handbills with details of the times and locations of the inns at which the coaches would stop, and the destinations they served.

Before the mail coach

When a public postal service was first introduced in England in 1635, letters were carried between ‘posts’ by post-boys on horseback and delivered to the local postmaster. The postmaster would then take out the letters for his area and hand the rest to another post-boy to carry them on to the next ‘post’. This was a slow process and the post-boys were an easy target for robbers, but the system remained unchanged for almost 150 years.

John Palmer, a theatre owner from Bath, had organised a rapid carriage service to transport actors and props between theatres and he believed that a similar scheme could improve the postal service. In 1782, Palmer sold his theatre interests, and went to London to lobby The Post Office. Despite resistance from senior Post Office staff, William Pitt, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, accepted the idea. An experimental mail coach journey, undertaken at Palmer’s expense, started from Bristol on 2 August 1784, at 4 pm, reaching London at 8am the next day, exactly on schedule. The success of the trial led Pitt to authorise other mail coach routes and by spring 1785, coaches from London served Norwich, Liverpool and Leeds. By the end of that year there were services to Dover, Portsmouth, Poole, Exeter, Gloucester, Worcester, Holyhead and Carlisle, and by 1786, the service had also reached Edinburgh. That same year, Palmer was made Surveyor and Comptroller General of the Post Office.

A revolution in communications and transportation

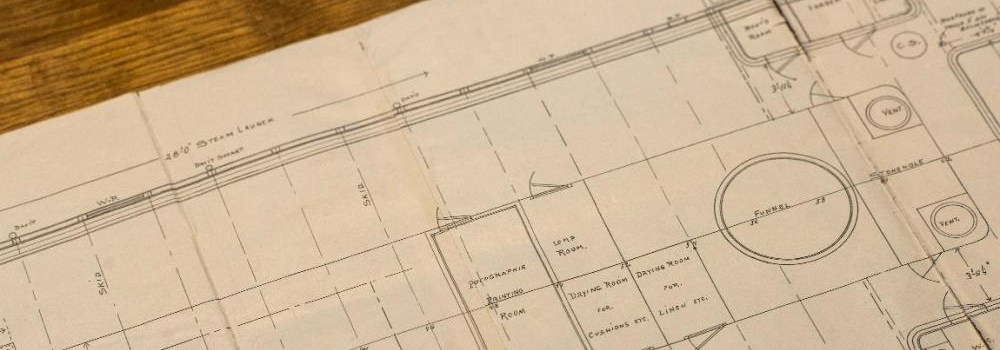

The mail coach, horses and the driver were all provided by contractors. Competition for the contracts was fierce. The first mail coaches were poorly built but an improved patented coach, designed by John Besant, was adopted by the Post Office in 1787, and by 1800, the Post Office had their own fleet of coaches with smart black and maroon livery. The only Post Office employee aboard the mail coach was the guard. He was heavily armed, carrying two pistols and a blunderbuss. He wore an official uniform of a black hat with a gold band and a scarlet coat with blue lapels and gold braid. He also had a timepiece, regulated in London to keep pace with the differences in local time, and recorded the coach’s arrival and departure times at each stage of the journey. The guard sounded a horn to warn other road users to keep out of the way and to signal to tollkeepers to let the coach through.

Initially, four passengers were carried inside the mail coach but later one more was allowed to sit outside next to the driver. The number of external passengers was increased to three with the introduction of a double seat behind the driver. No one was permitted to sit at the back near the guard or the box where the post was conveyed. Every morning, when coaches reached London, they were taken to a constructor’s works, usually Vidler’s, to be cleaned and oiled. In the afternoon, they were returned to the coaching inns, where horses were hitched up for journeys to all parts of the country. The mail coach services had exotic names that suggested their speed and novelty. The Quicksilver, The Defiance, The Rapid, The Age, The Eclipse, The Bee, The New Telegraph, The Rocket and The Hawk can all be found advertised in bills in the Archive collection, departing from inns in the City streets - Blossoms Inn (Cheapside), The Saracen’s Head (Snow Hill) and the exotic sounding La Belle Sauvage Inn (Ludgate Hill). Nathan Mayer Rothschild (1777-1836) newly arrived in the City in 1809, would have been sending letters to his business in Manchester, and to the ports of Southampton, Portsmouth and Folkestone on their way by fast ships to his brothers in Europe and agents across the globe, and also receiving letters sent to New Court; some of the bills in the Archive have been annotated with prices indicating that these services were used.

Outside London, coaches also made journeys between the main post towns. The coaches averaged 7 to 8 mph in summer and about 5 mph in winter but by the time of Queen Victoria the roads had improved enough to allow speeds of up to 10 mph. Fresh horses were supplied every 10 to 15 miles. The mail coach travelled faster than the stagecoach; the stage stopped for meals where convenient for its passengers, but the mail coach stopped only where necessary for postal business. Stops to collect mail were short and sometimes there would be no stops at all with the guard throwing bags of letters to the Letter Receiver or Postmaster from the coach and snatching the new deliveries of outgoing bags of mail from the postmaster.

Travelling on the coaches

Travel could be uncomfortable as the coaches travelled on poor roads and passengers were obliged to dismount from the carriage when going up steep hills to spare the horses, as Charles Dickens describes at the beginning of ‘A Tale of Two Cities’ (1859): “The Dover road lay, as to him, beyond the Dover mail, as it lumbered up Shooter’s Hill. He walked up hill in the mire by the side of the mail, as the rest of the passengers did; not because they had the least relish for walking exercise, under the circumstances, but because the hill, and the harness, and the mud, and the mail, were all so heavy, that the horses had three times already come to a stop, besides once drawing the coach across the road, with the mutinous intent of taking it back to Blackheath…”

Demise of the service

The development of the railways led to the end of the mail coaches, with trains first carrying mail on 11 November 1830, between Liverpool and Manchester. Other rail lines developed and by the early 1840s many London-based mail coaches were being withdrawn from service. The last regular London based coach service was the London to Norwich, via Newmarket, which ended on 6 January 1846. Mail coaches survived however on services between some provincial towns until the 1850s.

The day the Exeter mail coach was held up by a lion

These days the occasional vicious dog is the only obstacle delivery workers face when doing their rounds. But in October 1816, the Exeter mail coach, was attacked by something far more dangerous. While on its way to London, the mail coach drew into the Pheasant Inn on Salisbury Plain. The leading horse, named ‘Pomegranate’ was suddenly attacked by a lioness that had escaped from a Ballard's travelling menagerie which had stopped for the night nearby. The passengers fled in terror into the inn and locked themselves inside, shutting out the mail coach guard, Joseph Pike. Pike reached for his blunderbuss but was persuaded not to shoot the expensive lion by the menagerie owner who came rushing up to the scene. The lioness then turned her attentions to Pike’s Newfoundland dog which was then chased and killed by the beast. The lioness was eventually subdued and recovered from underneath a nearby granary. Despite the attack, the mail coach continued on to London (no doubt with its occupants fortified by a sustaining beverage or two from the inn), and the post arrived at its final destination just 45 minutes late.

Today, companies like Amazon, Yodel, DHL and Hermes (to name but a few) owe much to the pioneers of a cheap, regular and reliable delivery service. Delivery by drone would have seemed an unbelievable feat to the man armed with a blunderbuss on the back of the London mail coach, bumping over dirt tracks in the pouring rain!

RAL 000/573/19 volume of mail coach bills