The Rothschild Archive holds the evidence of a banking history dating from the early 19th century, documenting the innovations and evolution of the business of international finance.

Two hundred years of innovation

“If the House of Rothschild carries through a loan of whatever kind it may be, that fact will provide us with the necessary security”. Count Ficquelmont, Austrian Ambassador at Naples, to Prince Metternich, 1821.

The bond business

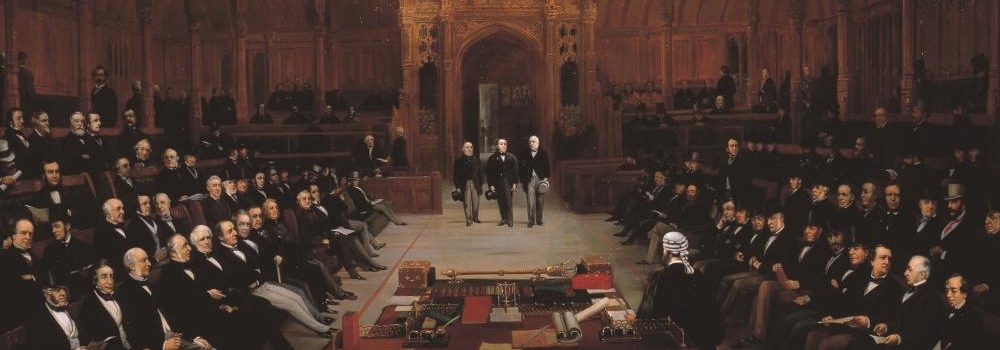

Banks and financiers have long lent money to governments, and so have individuals through investment in instruments such as the British government consols and French government rentes. However, the government bond, as developed by Nathan Mayer Rothschild (1777-1836) in London, for the first time made investing in governments overseas an attractive prospect for the individual. The Rothschild family's early work for governments and princes had begun in earnest during the Napoleonic wars, from providing a variety of financial services to their first important client, the Elector of Hesse, to supplying gold and silver coin to Wellington's armies and to handling Britain's subsidy payments to her wartime allies. Although the Rothschild businesses purchased bonds for their own account, and individual family members were also substantial investors in a private capacity, as contractors for a loan the banks' role was not principally as providers of capital. They were employed to lend their reputation to a bond issue, to negotiate terms, rates and prices, and to market the loan; in return they received commission. The bond, enshrining the contract between borrower and banker, was a valuable document: its holders were entitled to present attached coupons at prescribed intervals to receive interest on their investment, and present the bond itself for return of the principal on maturity.

1818 Prussian Government 5% Loan, £5m

Although the five sons of Mayer Amschel Rothschild (1744-1812) had arranged many loans for sovereign governments before 1818, the one issued by Nathan Rothschild in May of that year is the true precursor of the public borrowing which transformed the international capital market in the nineteenth century. The significance and novelty of the loan is several fold. It was raised in sterling, rather than Prussian thaler, and the interest could be payable in sterling in London and other financial centres; by these means currency risks were greatly reduced. This made it convenient and attractive for British investors, although in the event much of this issue was taken up by investors on the continent. Prussia also agreed to follow English practice and set up a sinking fund to amortise the loan, with regular remittances to London from the government to repay the capital. With a sinking fund to repay the principal, the schedule for eventual repayment was made explicit to the investor. These repayments were effected by purchase of the bonds in circulation; if the bonds were being traded ‘above par’ – that is, if their actual value was greater than their nominal value – then lots would be drawn to determine which bonds would be compulsorily redeemed at face value only. This would be the pattern for future bond issues from the bank. Significantly, the loan was issued not just in London but also in Frankfurt, Berlin, Hamburg, Amsterdam and Vienna, representing a major step towards the creation of a completely international bond market.

The Times did not exaggerate when it later described Nathan as 'the first introducer of foreign loans into Britain': “for, though such securities did at all times circulate here, the payment of dividends abroad, which was the universal practice before his time, made them too inconvenient an investment for the great majority of persons of property to deal with. He not only formed arrangements for the payment of dividends on his foreign loan in London, but made them still more attractive by fixing the rate in sterling money, and doing away with all the effects of fluctuation in exchanges.” The Times, 4 August 1836

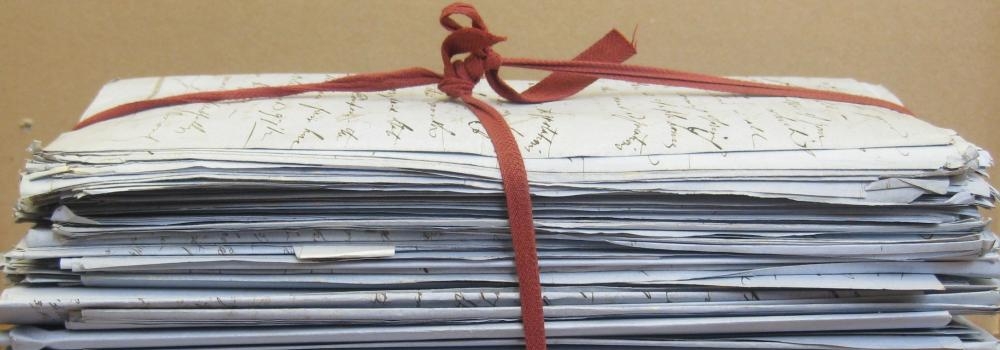

However, the loan nearly failed to materialise. Nathan had been working in association with the London representative of the Prussian Seehandlung bank, Barandon, and, inexplicably, Barandon had made the terms of the loan public before the contract was signed. The Prussian government withdrew from the negotiations to avoid the humiliation of being seen in need of credit on what had been revealed to be rather unfavourable terms. The five Rothschild brothers maintained an extensive correspondence with each other, writing in Judendeutsch, the German-Jewish dialect of Frankfurt using Hebrew script. Nathan’s brother Salomon berated him for working with a ‘coffee house gossip’ and for having ‘risked our excellent name with a public circular sent in conjunction with a stranger and a brandy dealer’. Nevertheless, Prussia had emerged from the Napoleonic wars £32,000,000 in debt and the government ultimately found no better offer than that of the Rothschilds. Salomon entered into some intensive behind-the-scenes negotiations with Prince von Hardenberg and Christian Rother, respectively the Prussian state chancellor and its finance minister, and the terms were modified in Prussia’s favour. The bond issue in March 1818 was a great success, and indeed Rother’s name features prominently in the ledger of subscribers to the loan, which is preserved in the Archive. The first tranche of the loan was sold at 70 per cent of its nominal value, and was soon trading well above that price. Within a month James, the youngest of the five Rothschild brothers, found the bonds in great demand in Paris and resolved to refrain from selling them until the price rose even further, writing to his brothers that ‘I shall throw away the key until they are 85’.

Further loans business

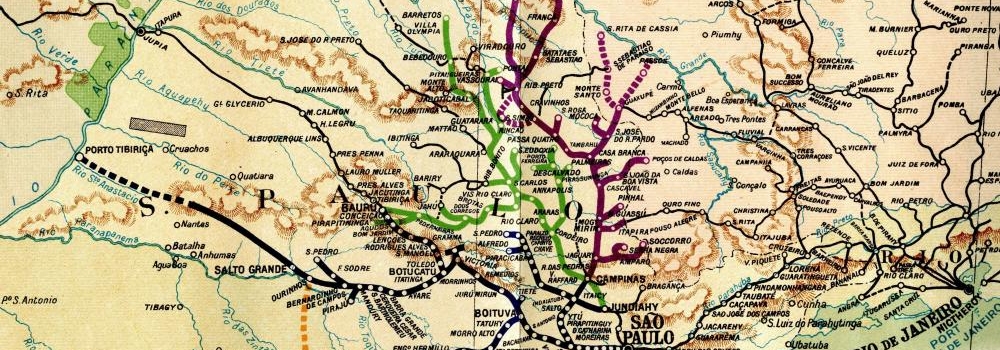

In 1822 Nathan won another contract for a loan to Prussia, for £3,500,000. The interest was again fixed at 5 per cent, but this time the issue price was 84, reflecting the success which Prussian credit had achieved in the international market place. The rate of interest, price of issue and subsequent market price of a bond have often been seen as 'opinion polls' of perceptions of a borrowing nation's creditworthiness, reflecting past performance in servicing loans, and contemporary views of a country's political and financial stability. Understanding this sensitive relationship was essential for success in this market, and the Rothschilds were famously well-informed and well-connected in the worlds of high finance, government and international diplomacy. Government bond issues following this model were the mainstay of the business of N M Rothschild & Sons in London until the Second World War and a significant feature of the business of the other Rothschild banking houses in Paris, Frankfurt, Vienna and Naples.

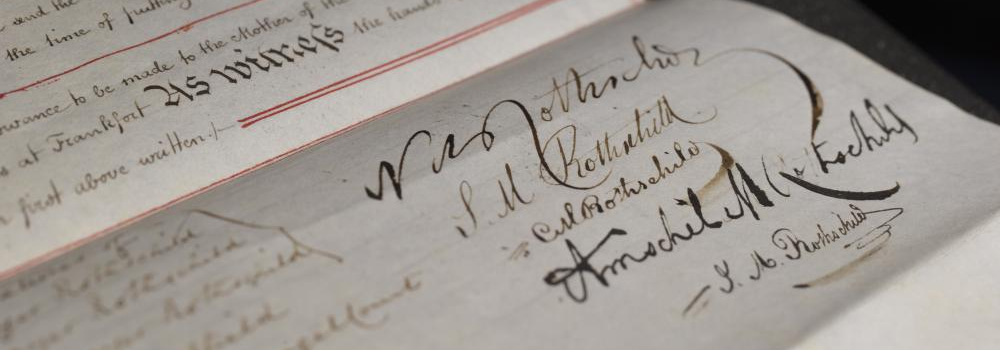

RAL VI/10/5