As a revolution hits our high streets with century-old names disappearing and fundamental changes in the way we purchase goods from jeans to washing machines, we look back to an almost forgotten but nonetheless momentous change in our shopping routines. The first few months of 1971 saw a transformation in our purses and wallets – the introduction of decimal currency, which had first been proposed in 1824.

The 15th of February 1971 was ‘Decimal Day’ in the United Kingdom; the day on which the country officially decimalised its currency of pounds, shillings, and pence (£sd). February had been chosen for Decimal Day because it was the quietest time of the year for the banks, shops, and transport organisations. Prior to this date, the British pound was made up of 20 shillings, each of which was made up of 12 pence, a total of 240 pence. With decimalisation, the pound kept its old value and name, but was now divided into 100 ‘new pence’, each of which was worth 2.4 ‘old pence’.

History of decimal currency

The Russian rouble was the first decimal currency to be used in Europe, dating to 1704, though China had been using a decimal system for at least 2000 years. Elsewhere, the Coinage Act of 1792 introduced decimal currency to the United States. In France, the decimal French franc was introduced in 1795.

Earlier efforts in the United Kingdom to introduce decimalised currency had failed; in 1824, Parliament rejected Sir John Wrottesley's proposals to decimalise sterling, which were prompted by the introduction of the French franc three decades earlier. Following this, little progress towards United Kingdom decimalisation was made for over a century. The Decimal Association, founded in 1841 to promote decimalisation and metrication, saw interest in both causes boosted by a growing national realisation of the importance of ease in international trade, following the 1851 Great Exhibition. In 1857, the Royal Commission on Decimal Coinage published a report on the benefits and drawbacks of decimalisation but failed to draw any conclusions on its adoption. A final report in 1859 from two commissioners, Lord Overstone and John Hubbard (Governor of the Bank of England), came out against the idea, claiming that it had "few merits". In 1862, the Select committee on Weights and Measures favoured the introduction of decimalisation to accompany the introduction of metric weights and measures.

The Royal Commission on Decimal Coinage (1918–1920), chaired by Lord Emmott, reported in 1920 that the only feasible scheme was to divide the pound into 1,000 mills (the pound and mill system, first proposed in 1824), but that it would be too inconvenient to introduce; other members recommended that the pound should be replaced by the ‘royal’, consisting of 100 halfpennies, with there then being 4.8 royals to the former pound.

It wasn’t until forty years later, in 1960, that a report prepared jointly by the British Association for the Advancement of Science and the Association of British Chambers of Commerce, followed by the success of decimalisation in South Africa, prompted the Government to set up the Committee of the Inquiry on Decimal Currency (The Halsbury Committee) in 1961, which reported in 1963. The adoption of the changes suggested in the report was announced on 1 March 1966. The Decimal Currency Board was created to manage the transition, but the plans were not approved by Parliament until the Decimal Currency Act of May 1969. The former Greater London Council leader Bill Fiske was named as the Chairman of the Decimal Currency Board. Consideration was given to introducing a new major unit of currency worth ten shillings in the old currency. Suggested names included the ‘new pound’, the ‘royal’ and the ‘noble’. However, Halsbury decided that the pound sterling's importance as a reserve currency meant that the pound should remain unchanged.

D-Day 1971: preparation and introduction

Under the new system, new coinage was issued alongside the old coins. The 5p and 10p coins were introduced in April 1968 and were the same size, composition, and value as the shilling and two-shilling coins they replaced. In October 1969, the 50p coin was introduced, with its old equivalent, the 10-shilling note withdrawn on 20 November 1970. This reduced the number of new coins required to be introduced on Decimal Day, meaning that the British public would already be familiar with three of the six new coins. The old halfpenny was withdrawn from circulation on 31 July 1969, and the half-crown (2s 6d) followed on 31 December to ease the transition. The smallest coin, the farthing (worth a quarter of an old penny), last minted in 1956, had already ceased to be legal tender in 1961.

A substantial publicity campaign took place in the weeks before Decimal Day, including a song by popular entertainer Max Bygraves called Decimalisation. The BBC broadcast a series of five-minute programmes, Decimal Five, to which The Scaffold contributed some specially written tunes. ITV repeatedly broadcast a short drama called Granny Gets the Point starring the character actress Doris Hare, in which an elderly woman, who does not understand the new system, is taught to use it by her grandson.

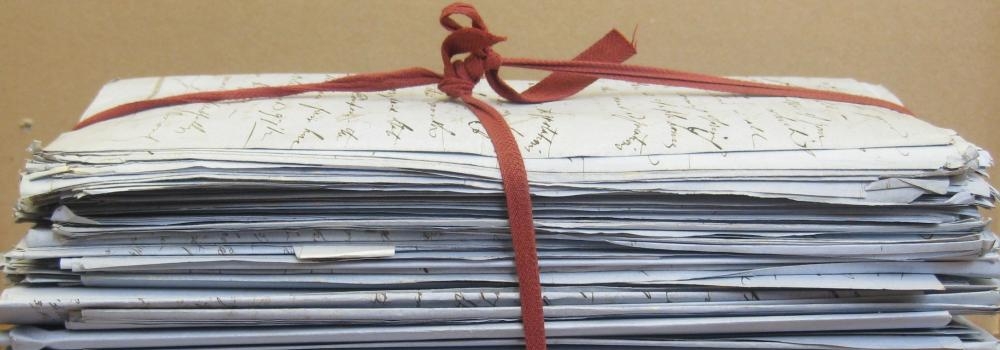

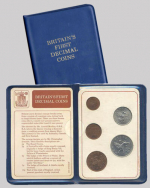

Banks received stocks of the new coins in advance, which were issued to retailers shortly before Decimal Day to enable them to give change immediately after the changeover. Banks were closed from 3.30 pm on Wednesday 10 February 1971 to 10.00 am on Monday 15 February to enable all outstanding cheques and credits in the clearing system to be processed and customers' account balances to be converted from £sd to decimal. In many banks, the conversion was done manually, as few bank branches were then computerised. Many items were priced in both currencies for some time before and after the change. Commemorative proof sets of the new currency such as this one in the Archive collection were produced together with ‘handy calculators’ to help the public easily understand the new values.

After Decimal Day

Due to extensive preparations and the publicity campaigns organised by the British government, Decimal Day itself went smoothly. Criticism that some traders had taken advantage of the transition to raise their prices were levelled, despite the fact that in the latter case, overall price adjustments slightly favoured the consumer. After 15 February, shops continued to accept payment in old coins but always issued change in new coins. The old coins were then returned to banks, and quickly taken out of circulation.

The government intended that the new units would be called ‘new pence’; however, the British public quickly began to refer the value as ‘pee’ when shortened, with ‘10p’ pronounced as ‘ten pee’ instead of ‘ten new pence’. It wasn’t until 1982 that the word ‘new’ was removed from the inscriptions on coins and was replaced by the number of pence in the denomination. Thus the old names of ‘tuppence’, ‘tanner’ and ‘shilling’ ‘florin’ etc. were consigned to the history books, although amounts denominated in guineas (21 shillings or £1.05) were reserved still for specialist transactions, and continued to be used in the sale of horses and at some auctions.

The phrase "How much is that in old money?" became associated with those who struggled with the change, and continues to be used as a colloquialism by those of a certain age when referring to conversions between metric and imperial weights and measures, and when challenged with new and unfamiliar situations!

Read more about Decimalisation on the website of The Royal Mint Museum: Celebrating 50 years of decimal currency »

RAL 000/2714 Souvenirs of decimalisation, c.1971