Through their philanthropy and patronage, the Rothschild family supported many causes. These included social enterprises such as schools, hospitals and other charities, but their interests were broad ranging, and they gave their support to the great heroic endeavours of their time.

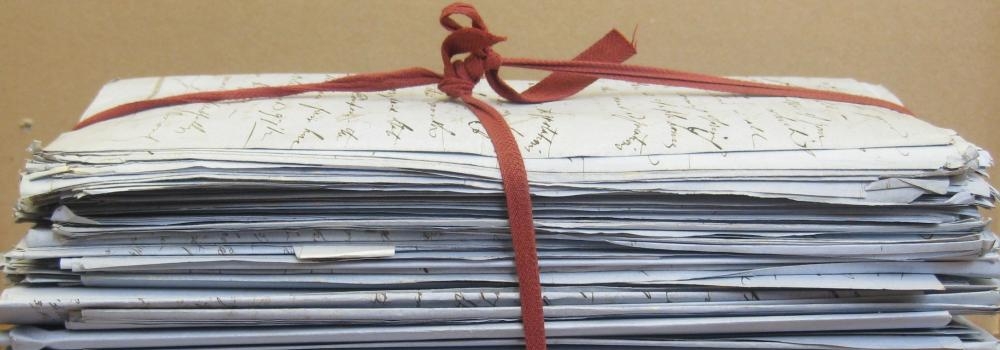

In November 1914, Marie, Mrs Leopold de Rothschild (1862-1937) received this heartfelt thank-you letter from the polar explorer Ernest Shackleton (1874-1922).

The Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition

South Georgia 15.11.14

Dear Mrs Rothschild,

On the eve of my departure from this sub-antarctic island for the polar ice, I dictate this farewell line to once more thank you for the great assistance you have given this expedition and to assure you that all we can do to make it a success will be done.

Yours very truly

E.H. Shackleton

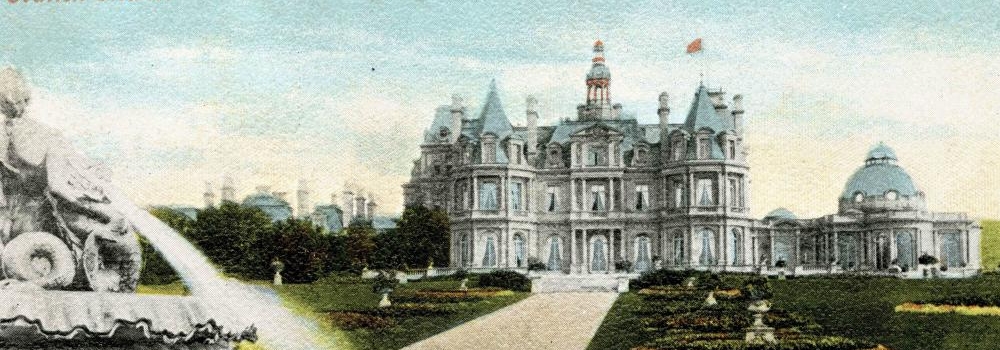

Marie de Rothschild (née Perugia) was the daughter of a Trieste merchant. She married Leopold de Rothschild (1845-1917) in 1881, at a ceremony noted for the beauty of the bride, and the attendance of the then Prince of Wales. The couple made their home at Gunnersbury Park and Ascott House. They had three sons, Lionel Nathan (1882–1942), Evelyn Achille (1886–1917), and Anthony Gustav (1887–1961). Throughout her life, Marie supported many medical charities, and served on hospital boards. In 1920, she was presented with a CBE for her war work with the British Red Cross.

Ernest Shackleton was one of the principal figures of the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration. Born in Kilkea, Athy, County Kildare, Ireland, the family moved to Sydenham in London when he was ten. He left school at 16 and went to sea; his first experience of the polar regions was as third officer on Captain Robert Falcon Scott's Discovery Expedition, 1901–1904. During the second expedition of 1907–1909, which Shackleton led, he and three companions stablished a new record reaching the largest advance to the pole in exploration history, and he climbed Mount Erebus. For these achievements, he was knighted by the King on his return home. After the race to the South Pole ended in December 1911 with Roald Amundsen's conquest, Shackleton turned his attention to Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition of 1914–1917.

The Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition

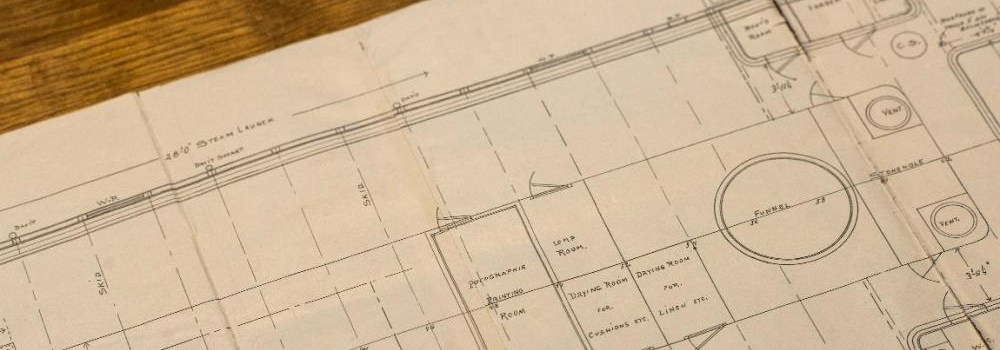

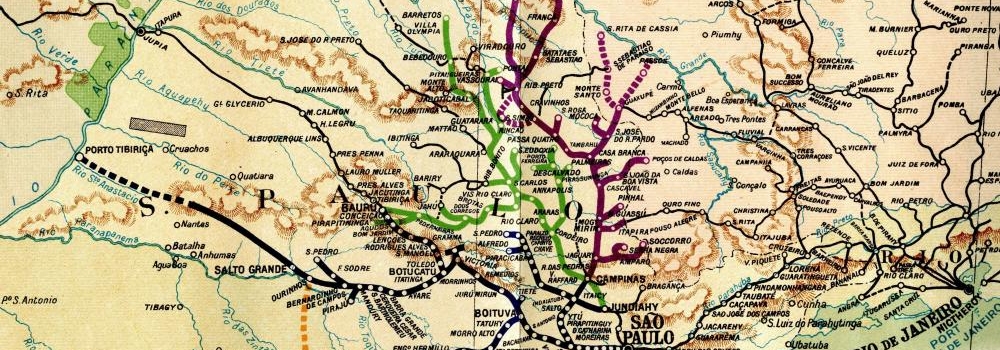

This Expedition, also known as The Endurance Expedition was an attempt to make the first land crossing of the Antarctic continent. The crossing remained, in Shackleton's words, the "one great main object of Antarctic journeyings". He proposed to sail to the Weddell Sea and to land a shore party near Vahsel Bay, in preparation for a transcontinental march via the South Pole to the Ross Sea. According to legend, Shackleton posted an advertisement in a London paper, stating: "Men wanted for hazardous journey. Low wages, bitter cold, long hours of complete darkness. Safe return doubtful. Honour and recognition in event of success”. The expedition was to consist of two parties and two ships; Endurance under Shackleton for the Transcontinental Weddell Sea party, and Aurora, under Aeneas Mackintosh, for the Ross Sea party. Disaster struck when Endurance became trapped in pack ice throughout the Antarctic winter of 1915 and was slowly crushed; the crew escaped by camping on the sea ice until the ship disintegrated, then by launching the lifeboats to reach Elephant Island and ultimately the inhabited island of South Georgia, a stormy ocean voyage of 800 miles. On the other side of the continent, Aurora was blown from her moorings during a gale and was unable to return, leaving the Ross Sea party shore party marooned without proper supplies or equipment; three lives were lost before their eventual rescue.

Preparations, finance and legacy

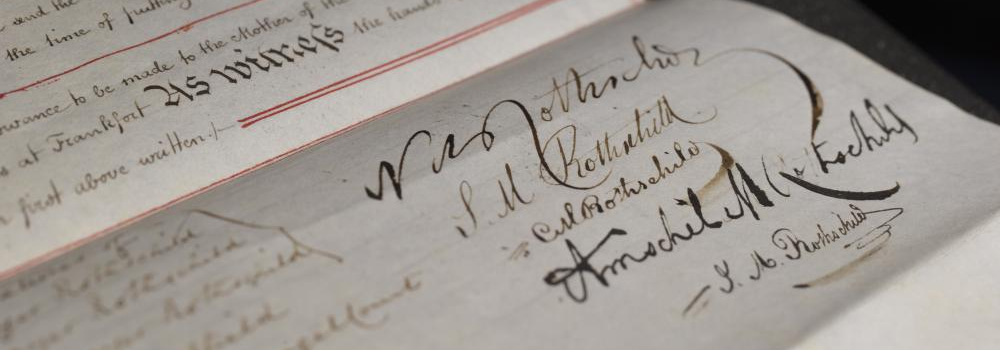

Early in 1913, Shackleton initiated preparations for his Expedition, and in December, he made his plans public in a letter to The Times. He estimated that he would need £50,000 (over £4.5 million today). The Royal Geographical Society gave £1,000, and the Government offered £10,000, provided Shackleton could raise an equivalent amount from private sources. He began to solicit contributions from wealthy backers, and approached the former Prime Minister Lord Rosebery, (who had married Hannah de Rothschild (1851-1890) in 1878), but received only the blunt reply: "I have never been able to care one farthing about the Poles"; Rosebery later donated £50. Other backers included the playwright J. M. Barrie, Dudley Docker of the Birmingham Small Arms Company, the tobacco heiress Janet Stancomb-Wills, the industrialist Sir James Caird, - and the Rothschilds. How this contact first came about is not known. During the early 1900s, Shackleton had developed a number of unsuccessful business schemes which may have come to the attention of the Rothschilds, and he shared their politics, having unsuccessfully stood in the 1906 General Election as the Liberal Unionist Party's candidate for Dundee. It may also have been through Marie’s adventurous young sons that his endeavours were promoted. The Daily Mail later estimated that he had been able to raise over £80,000.

When Shackleton returned to England in May 1917, Europe was in the midst of the First World War, but his Antarctic feats were greeted in Britain with great enthusiasm. Most of the returning members of the expedition took up immediate active military or naval service; Shackleton although in poor health, volunteered for the army, and saw service in the Russian Civil War, before embarking on the lecture circuit. In 1921, he returned to the Antarctic with the Shackleton–Rowett Expedition, but died of a heart attack while his ship was moored in South Georgia in 1922. At his wife's request he was buried there.

His expedition of 1914, although failing to accomplish its objective, became recognised as an epic feat of endurance, and it would be more than 40 years before the first crossing of Antarctica was achieved, by the Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition, 1955–1958.

RAL 000/1373/10/3