Early years 1852-1914

The use of gold and gold coin in trade and finance in the early 19th Century meant that there was a 'growth industry' for the brokers and refiners of gold. By the 1830s there were two brokers - Mocatta & Goldsmid and Sharps, the former being by far the oldest and the more influential. The refining of gold was in the hands of several firms such as Browne & Wingrove and P.N. Johnson, the forerunners of Johnson Matthey. The Royal Mint itself was also engaged in both refining and the historical role of striking gold coin.

The rivalry between Nathan Mayer Rothschild (1777-1836) and, in the 1820s, Jacob Mocatta and in the 1830s Isaac Goldsmid, led to Nathan trying to break the almost complete monopoly of those firms. The first step was to avoid the payment of brokerage on bullion by dealing direct with the Bank of England. When the collapse of several banks in 1825 led to a run on the Bank of England, it was Rothschilds who came to the rescue with gold purchased from European banks through the family connections.

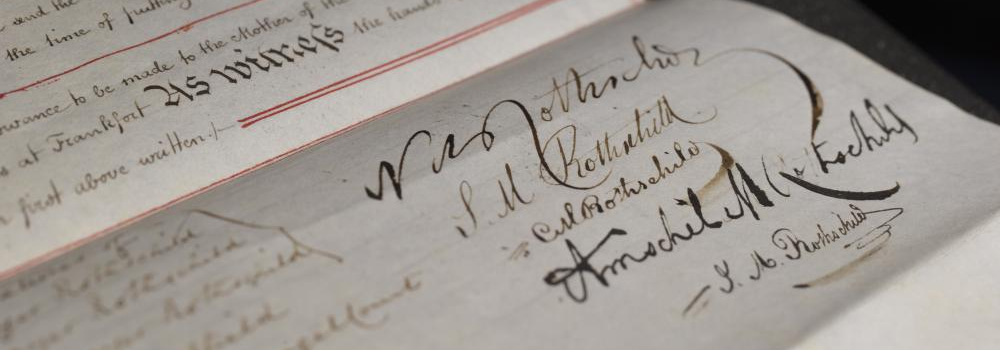

New discoveries of gold in the 1840s and 1850s brought opportunities to gain control over the means of production. The report of a Royal Commission of 1848, charged with examining the efficiency of the Royal Mint, contained recommendations for the separation of the twin roles of refining and coin-striking. Previously the Company of Moneyers monopolised the coinage work under contract to the Master of the Royal Mint who, acting as an agent for the Crown, also contracted with private individuals for the melting and refining of precious metals within the same premises. It was the lack of clearly defined areas of public and private work that led to the refining being 'hived off' and offered to interested parties on a leasehold basis. Curiously, the offer was not snapped up by Mocatta & Goldschmid; the opportunity to manage a refinery in England was enthusiastically seized by Anthony de Rothschild (1810-1876), the second son of Nathan. On 26 January 1852 he wrote from New Court to the Deputy Master of the Mint: “I request you will have the goodness to inform the Master of the Mint that I am ready to execute the Lease for the Refinery, and I should be obliged to you to let me know when you receive the confirmation of the Chancellor of the Exchequer to the conditions of the Lease, in order that the documents relative to it may be completed.” On 3 February the lease of the buildings and equipment was sanctioned by Her Majesty’s Treasury and the Royal Mint Refinery became part of the London business’s interests. The acquisition of the Refinery lease was an important step in the plan to make Rothschilds a leader in the London bullion trade.

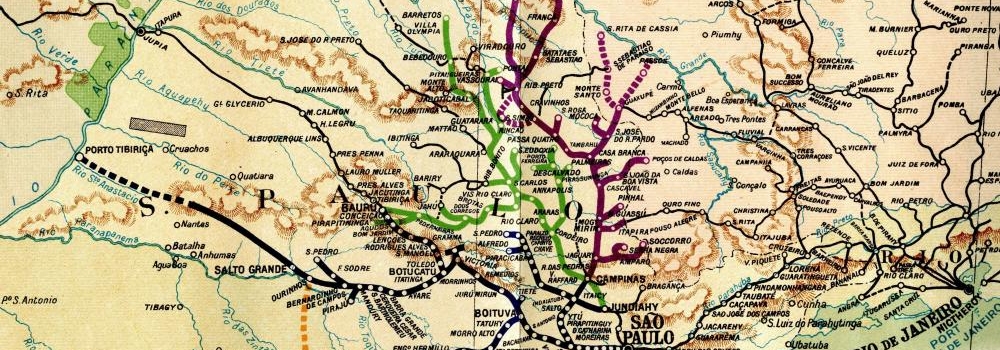

By 1860, the Royal Mint Refinery was fully established and in a position to compete for the work arising from the discovery of more new goldfields throughout the world. After the Californian 'rush' of 1849 came the Australian fields in the 1850s followed by the South African discoveries in 1884. Each area brought its own challenges with regard to refining - in the Klondike, gold dust was used as a raw currency but demands for more sophisticated means of movement of gold led to more refineries being built.

The operations of the Royal Mint Refinery

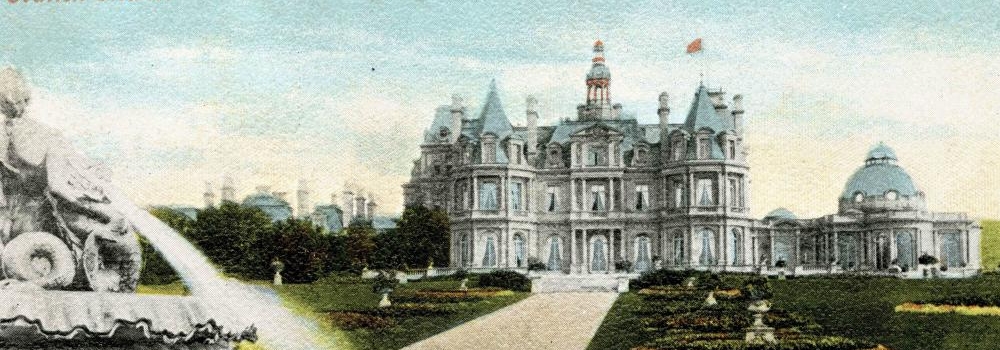

The Royal Mint Refinery was located in London’s east end. Gradually the freeholds were acquired for various houses in Rosemary Lane (now Royal Mint Street) and others in the lanes and courts leading off such as Seven Star Court, Becks Rent and the stabling in St. Peters Court. Some of these buildings were converted into offices whilst others were maintained as cottages by Sir Anthony for Refinery employees. By 1911 there were 33 flats available in adjoining properties and these were granted to married men according to seniority.

The old methods of roasting ores and combining with mercury gave way to improvements using sulphuric acid but the problem of dispersing fumes without upsetting the neighbours remained for many years. In one exchange of letters the manager of the Refinery wrote to the Deputy Master of the Mint that it was hoped that a new chimney would be the answer but it always seemed to be worse in the "mauvais temps". The reason for writing in French was the practice of using experienced workmen from an area north of Paris where these skills were already established together with other specialists recruited from Belgium by the first manager. There was a succession of French and Swiss managers of the refinery with names such as Poisat, Bertrand, Arnould, Dudoit Buess. In 1937 the first manager with an English name was appointed, a Mr. Smith.

The records for this early period in the development of the refinery contain notes in French passed between Poisat, Gallez (the engineer responsible for the new techniques) and Sir Anthony de Rothschild with requests and drafts for expenses or part payments to Messrs William Cubitts. The latter were one of the largest of the Victorian construction firms and it was fitting that they were employed by the House in this new venture. Further developments in the refining of silver brought in more equipment from Europe, such as Moebius Cells for producing much higher standards of purity to meet the demands of industry. Apart from fresh inflows of precious metals from new fields, monetary crises led to demands for the refining of coin to recover their contents.

The Royal Mint Refinery 1890-1914

By the 1890's the success of the refinery operations led to Rothschilds acquiring the freehold of the premises which, from the establishment of the refinery in 1852, had been leased by them. This was done under the aegis of Charles Rothschild (1877-1923), the younger son of Nathaniel, 1st Lord Rothschild (1840-1915). Charles promoted research into new methods; in 1908 Comptoir Lyon-Allemand of Paris wrote a report for him on the separation of gold and platinum by electrolytic methods. Until 1918 the old sulphur method of gold refining had been used at RMR with its by-product of copper sulphate, but the more efficient method of refining by passing chlorine through molten gold ores had been in use in the Sydney Mint as early as 1867.

The First World War

By the end of the First World War the South African mines which had been the leading customers of the Refinery decided to build their own refinery, partly to cut losses due to U-boat activity. Ironically, the idea of building a refinery in the Rand itself had been suggested by Charles to his father before the War but it was turned down. It was essential that the Royal Mint Refinery kept up with developments and following the introduction of chlorine refining in 1918 a Lodge-Cotterall plant was built, substantially reducing the loss of gold and silver from the chimneys. Other possible losses were reduced by such means as burning the sabots and aprons worn in the foundry, sweeping the roof and draining all the rain-water into one settling tank. The mud cake from this last-named could yield gold at the rate of 15 troy ounces per ton.

After the death of Charles Rothschild in 1923 the family interest was maintained by Lionel de Rothschild (1882-1952) and later by Anthony de Rothschild (1887-1961) Lionel was senior partner until his death in 1942 and it was during these years that the refinery had to combat the Depression and make considerable changes in plant and buildings. Anthony was concerned with these developments and the problems brought about by the demands of the Second World War.

The 1930s

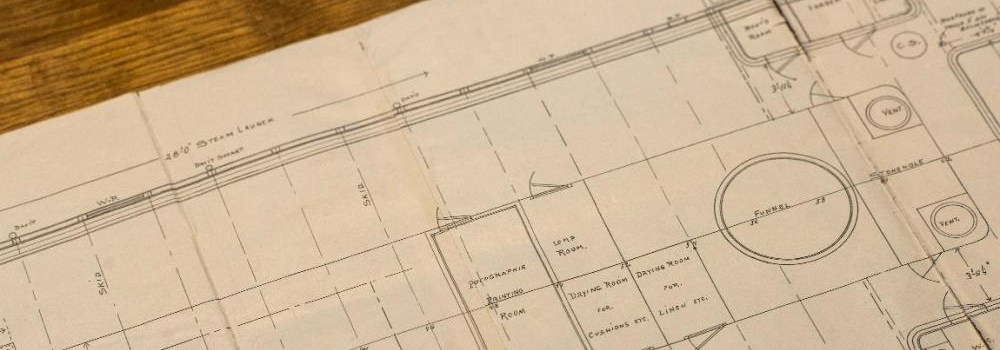

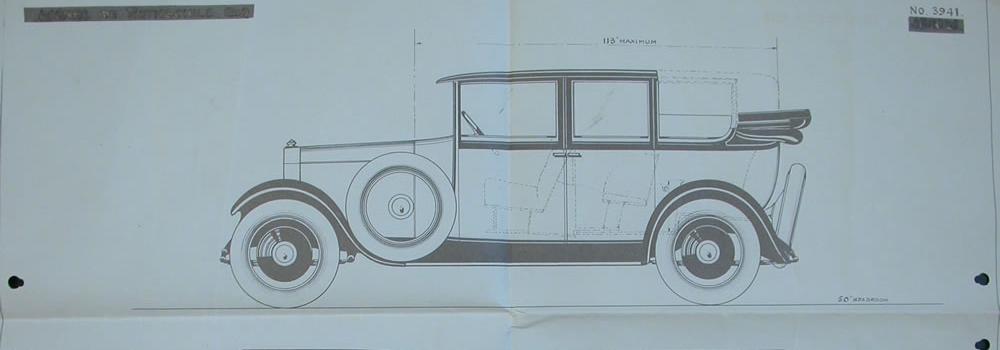

In 1884, Alfred de Rothschild (1842-1918), a younger brother of Nathaniel, 1st Lord Rothschild, had acquired from the Metropolitan Board of Works a freehold plot in Cartwright Street, off Royal Mint Street, on the understanding that it would be retained for a period of eighty years for the express purpose of building and maintaining suitable ‘Artisans Dwellings adequate to accommodate at least 100 persons’ thus providing suitable flats for the workmen at the refinery. By the early 1930s it was realised that working conditions had changed considerably. Many of the French families had moved away by 1914, and after the First World War, British workmen preferred to live away from their place of work. In 1936 plans were drafted for the complete replacement of a large part of the Refinery in both Cartwright Street and the original frontage in Royal Mint Street (formerly Rosemary Lane). The new structure would provide Messing, Changing, Cooking, Rest Rooms and other facilities. A small number of flats would be built for senior employees to retain the spirit of the original terms of 1884. Over the next two years these plans were developed and put into effect with as little interruption to the work as possible.

Whilst all these changes were taking place the financial world was going through some traumatic changes. Gold and silver were subjected to pressures never dreamt of before the war as one country after another succumbed to economic crises. The foundry was in continuous production to keep pace with the demand. The loss of the work from the Rand was offset by the growth of the goldfields in West Africa. This work continued, in spite of the Depression in many other industries, even after 1931 when the United Kingdom went off the Gold Standard.

Since the beginning of the century India had imported large quantities of gold because it was traditionally preferred to any other asset. Indian agricultural problems in the late 1920s led to a reversal of the tide which accelerated after 1931 so that huge shipments of gold left India for the London markets continuously until 1939. In addition to refining and casting of the standard gold bars with a minimum assay of 995.0 parts per thousand pure gold, coin of assays such as 900.0 or 916.7 were melted together and cast in larger bars to provide the equivalent fine gold content of the market bars but diluted by the copper which was commonly the balance metal in gold coins. A straightforward melting operation made for greater convenience of handling and shipping. Thus thousands of sovereigns, eagles and Napoleons were sold for cash and disappeared into the melting pots.

In 1936 the Royal Mint had started production of Maria Theresa thalers, originally supplied by the Austrian Mint prior to their sale of the dies to the Italian Mint in 1935. This subsequently led to shortages of this anachronistic trade dollar in East Africa and the Red Sea countries, hence the call on the Royal Mint together with the French and Belgian mints to fill the gap with copies when the Abyssinian War started. Old coin was to be refined and processed into new coin and to cope with this novel demand the refinery not only undertook silver refining but installed rolling mills necessary to assist the Royal Mint keep up its production. One benefit of this contract was the small amount of gold present in the old silver coins which could be recovered by the new electrolytic methods. The rolling mills came into existence in time to provide more of the diversified products which were later required during the Second World War.

The Second World War

Victor, 3rd Lord Rothschild (1910-1990) became involved in the affairs of the refinery from 1935 and during the war years, when he brought his scientific experience and contacts to the benefit of the refinery. The onset of war meant greater diversification for the refinery, although the bullion work continued, especially gold, where small bars were in demand for India. The rolling mills changed to brass strip for armaments, cupro-nickel for shell cases and such items as thin copper strip for aero-engine radiators, the latter in response to the realisation that the only source of supply was Birmingham, the target of the enemy raids. A new manager was appointed in 1938, Bill Williams, a chemist who had already been joined by another university-trained chemist, Peter Steel. As the war progressed, so the demand for new products grew and it largely fell to these two men to find ways of producing the answers. Early in the war it was found that wire-plated materials were at risk because the main supplier was the United States and a substitute source had to be found. The solution was the opening of a wire-plating department.

Being on the boundary between the City and the East End, with the docks to the south and railways to the north, meant that the refinery was in the heart of the bombing area of the Blitz. However, the refinery was fortunate in that it was not hit by bombs, unlike its neighbours on all sides including the Royal Mint. Incendiaries were a problem but apart from some scorch marks on the roof there was little to show. The Fire Watch Logbook, preserved in The Rothschild Archive records the raids, the damage to surrounding areas and other information culled from the newspapers.

Work was frequently interrupted by raids and the watchers had to take note of warnings from the local ARP officers and then decide on the level of action to take; whether or not to send everyone to the shelters to close down certain operations. When the flying bombs started there was an interesting entry in the log for 13th June 1944 where the observer had described a plane on fire which exploded on impact, not having had a chance to unload its bomb-load. This entry was annotated a few days later ‘perhaps the first sighting of a flying bomb’. Later that summer it was noticed that the twin chimneys of Greenwich power station provided a very useful indication of which route the V1s were taking - either side of the chimneys there was nothing to worry about, but if it flew between then take cover, quick!

The 1950s and 1960s

The end of the war naturally brought changes to the refinery. Those who had been away on war service returned and other ex-servicemen joined as new staff members. The range of products created in response to the demands of war had to be adapted to the needs of peace and, with this aim in sight, an agent was appointed. S. Goodfellow was experienced in this field and became involved in the export side and together with John Perry brought about the appearance of the Royal Mint Refinery at the British Industries Fair in Birmingham in the 1950s. Post-war governments were very much concerned with the promotion of exports and the stand at the Fair was maintained for several years.

In 1952 there was a celebration - a hundred years of activity, growing from a single purpose gold refinery to a variety of materials ranging from gold to brass, from bars of silver weighing 33 kilos or more to copper foil as thin as tissue paper, wires plated with all kinds of other metals, solders for industry, gold and silver grain for the jewellery trade, and metal screens for high volume printing.

Towards the end of the fifties many of the post-war problems were still in evidence. The crises of Korea, Suez and Hungary and conflicts in South East Asia and Israel continued to bring stress to the markets. The demand for small gold bars rose and fell as each crisis emerged and was then discounted or resolved. As other countries restored their industries so the competition grew and the diversity of operations created as part of the war effort now became a source of concern. A period of reviews starting in 1961 led to new accounting methods being introduced and schemes were considered whereby parts of the business might be hived off and sold to other more specialised firms.

The end of the Royal Mint Refinery under Rothschild ownership

Whilst much time and money had been spent on research and successful development, in the mood of the 1960s, the refinery was becoming an unusual area in which a merchant bank would be involved. The possibility of going back to a purely precious metals foundry but in a different location was investigated without success. In addition to the relationship with the Bank of England as an agent and the ex-officio chairmanship of the Gold Market there was also the responsibility of upholding the standards of the Market.

In 1965 the copper foil plant was sold to Brush Clevite who moved the equipment and some of the staff to Southampton. Two years later the remainder of the entire business was sold to Engelhard Industries Limited. The twelve months from October 1967 onwards saw a hectic period of activity. Everything had to be considered as to whether it went to the new works or was it to be scrapped or sold. The door stop in the bullion room was assayed because no one was quite sure where it came from and it could possibly have been an old coin bar. The wood blocked floor produced a worthwhile quantity of metal. Eventually the accumulated trappings of one hundred and fifteen years were all sorted out, people went off in various directions - some to Engelhard, some to New Court, some retired whilst others opted for redundancy - and the day came in early November 1968 when Spencer Richards became the last Rothschild employee to leave the building empty and close the gate on 19 Royal Mint Street.

In January 2015, The Royal Mint (the government-owned mint that produces coins for the United Kingdom) revived the brand 'The Royal Mint Refinery' to produce gold and silver bars under its 'refinery' brand. This was the first time since 1968 that the public was able to own bars imprinted 'RMR'. This business, and these gold and silver bars, have no connection to the Rothschild businesses.