The 'Waterloo Commission'

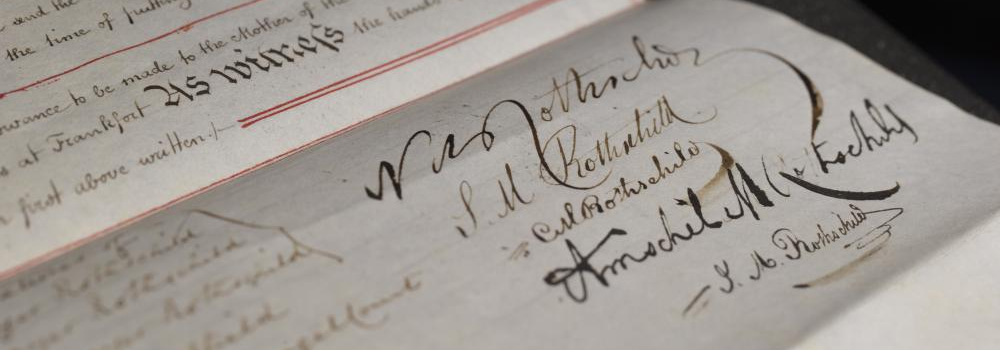

The Rothschilds supplied gold to the Duke of Wellington during the Napoleonic wars, rescuing Wellington’s armies from almost certain defeat. Between 1793 and 1815, Britain was almost continuously at war with France, placing a huge burden on the British Exchequer. By 1813, Wellington’s armies had succeeded in driving the French back to the Pyrenees, but the financial situation had become critical. Wellington desperately needed gold and silver coins, which could be exchanged locally to pay and feed his troops and so sustain morale. J.C. Herries, the Commissary in Chief to the British government, was responsible for financing and equipping the British armies in the field. Herries sought an intermediary who could secretly obtain large amounts of gold, but without alerting the French. In January 1814, he formally engaged Nathan Mayer Rothschild.Over the previous five years, Nathan had built an extensive network of couriers, dealers, brokers and bankers to facilitate his trading activities in gold. In the process, he established a commanding position as a bullion broker in the City of London. On receiving the commission from Herries, Nathan instructed his brothers on the continent to buy gold wherever they could, secretly and in small quantities, so as not to disturb the market. Once amassed, the gold was shipped and conveyed to Wellington in southern France, enabling him to pay his troops.

In 1815, following Napoleon’s escape from Elba, the need for finance for Wellington’s armies arose once more. Nathan was again successful in meeting the demand, raising immense sums of money in a short space of time and proposing that bullion be melted down to compensate for the shortage of coins. Drawing on finance raised by the Rothschilds, Wellington was able to pay the 209,000 English, Dutch and Prussian soldiers that had assembled in Belgium and subsequently defeated Napoleon at Waterloo.

Rescuing the Bank of England

As he rose to prominence, Nathan Mayer Rothschild cultivated a strong and close relationship with the Bank of England. During much of the early 1820s, Nathan was a buyer and borrower of both gold and silver from the Bank. In late 1825, the Rothschilds averted a financial crisis by supplying a large volume of gold to the Bank of England when the Bank ran desperately short of coined gold. Under Britain’s system of ‘cash payments’, bank notes could be fully and freely conver ted into gold at the Bank of England. This system had been restored in 1821, after a long absence. However, by 1825, Britain was running a trade deficit, leading to substantial outflows of gold from the country and a sharp monetary contraction. This, in turn, triggered a collapse in asset prices and the failure of a number of commercial banks. By mid-December, “an indescribable gloom was diffused through the City,” according to The Times. The Bank of England’s gold reserves were almost completely exhausted and the suspension of cash payments was imminent, threatening widespread financial turmoil. The rescue of the Bank was a remarkable achievement which owed everything to the international nature of the Rothschilds’ operations.

Refining and mining

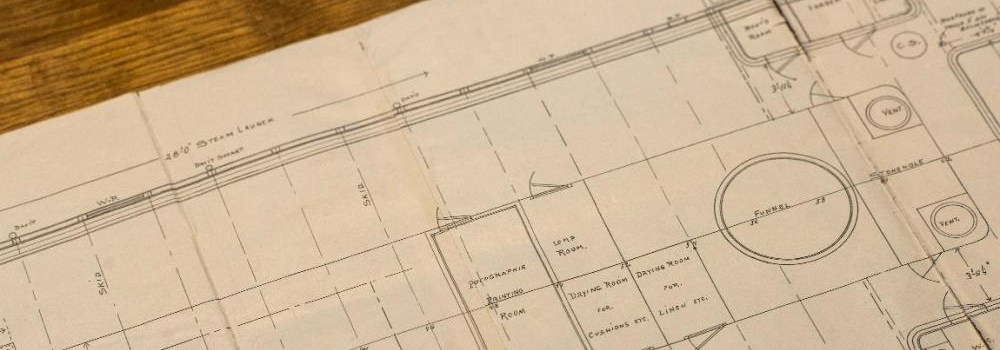

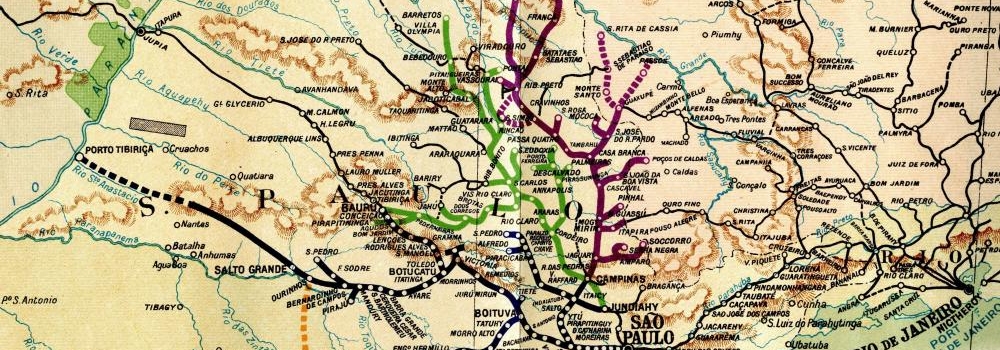

In 1830, to settle a default on a loan, the Spanish monarchy handed the Rothschilds the rights to the output of the Almadén mercury mines in south-west Spain. At the time, mercury was an essential component in the refining of gold. With the rights to these mines, the Rothschilds had a virtual global monopoly and therefore significant control over the gold refining process. The Rothschilds’ interests in refining can be traced to 1827, when James de Rothschild began operating his own refinery in Paris. The family’s interests expanded greatly in 1852 when they acquired the lease of the Royal Mint Refinery in London, a lease they retained for well over a century. The Royal Mint played a leading role in refining the world’s gold output and the acquisition was particularly timely as new discoveries of Californian and Australian gold brought a flood of new supplies to London in the 1850s.

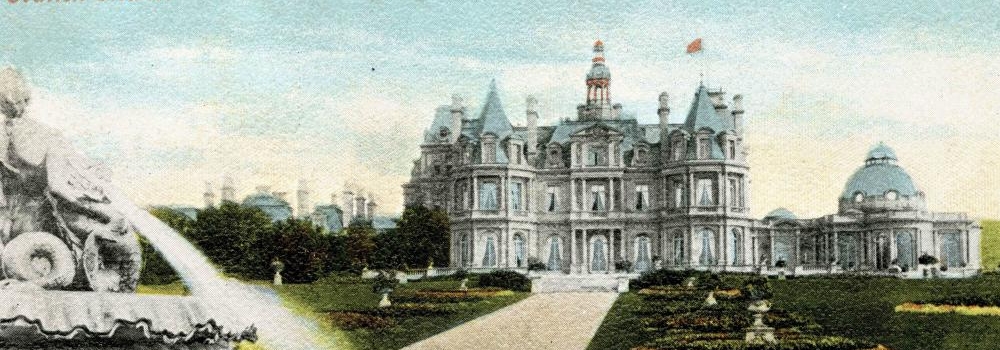

The gold fixing

The fixing provides a recognised daily gold price that is used as a benchmark throughout world markets. For much of its life, it has been a restrained affair, with five participants each sending representatives to Rothschild’s offices. From there, they telephoned their trading rooms and raised a small Union Jack when conferring with colleagues; only when all the flags had been lowered could the gold price be ‘fixed’ or agreed on. The fixing was held at the Rothschild Bank offices from 1919 until 2004.